So this is my first entry in the Philosophy series. I will be giving my opinion on stoicism at the end. The next entry is still undecided. Happy Chinese New Year to my readers.

Stoicism

Introduction

The term “Stoicism” derives from the Greek word “stoa,” referring to a colonnade, such as those built outside or inside temples, around dwelling-houses, gymnasia, and market-places. (To simplify it is a long pillar foundation) They were also set up separately as ornaments of the streets and open places. The simplest form is that of a roofed colonnade, with a wall on one side, which was often decorated with paintings. Thus in the market-place at Athens the stoa poikile (Painted Colonnade) was decorated with Polygnotus’s representations of the destruction of Troy, the fight of the Athenians with the Amazons, and the battles of Marathon and Oenoe. Zeno of Citium taught in the stoa poikile in Athens, and his adherents accordingly obtained the name of Stoics. Zeno was followed by Cleanthes, and then by Chrysippus, as leaders of the school. The school attracted many adherents, and flourished for centuries, not only in Greece, but later in Rome, where the most thoughtful writers, such as Marcus Aurelius, Seneca, and Epictetus, counted themselves among its followers [1]

History

Stoicism first appeared in Athens in the period around 300 B.C. and was introduced by Zeno of Citium. It was based on the moral ideas of Cynicism (Zeno of Citium was a student of the important Cynic Crates of Thebes), and toned down some of the harsher principles of Cynicism with some moderation and real-world practicality. During its initial phase, Stoicism was generally seen as a back-to-nature movement, critical of superstitions and taboos (based on the Stoic idea that the law of morality is the same as Nature).

Zeno’s successor was Cleanthes of Assos (c. 330 – 230 B.C.), but perhaps his most influential follower was Cleanthes’ student Chrysippus of Soli (c. 280 – 207 B.C.), who was largely responsible for the moulding of what we now call Stoicism. He built up a unified account of the world, consisting of formal logic, materialistic physics and naturalistic ethics. The main focus of Stoicism was always Ethics, although their logical theories were to be of more interest for many later philosophers.

Stoicism became the foremost and most influential school of the Greco-Roman world, especially among the educated elite, and it produced a number of remarkable writers and personalities, such as Panaetius of Rhodes (185 – 109 B.C.), Posidonius (c.135 – 50 B.C.), Cato the Younger (94 – 46 B.C.), Seneca the Younger (4 B.C. – A.D. 65), Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius.

Neo-Stoicism is a syncretic (This is a union or attempted fusion of different religions, cultures, or philosophies) movement, combining a revival of Stoicism with Christianity, founded by the Belgian Humanist Justus Lipsius (1547 – 1606). It is a practical philosophy which holds that the basic rule of good life is that one should not yield to the passions (greed, joy, fear and sorrow), but submit to God. [2]

Scholars usually divide the history of Stoicism into three phases:

- Early Stoa, from the founding of the school by Zeno to Antipater.

- Middle Stoa, including Panaetius and Posidonius.

- Late Stoa, including Musonius Rufus, Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius.

No complete work by any Stoic philosopher survives from the first two phases of Stoicism. Only Roman texts from the Late Stoa survive [3]

Doctrine

When considering the doctrines of the Stoics, it is important to remember that they think of philosophy not as an interesting pastime or even a particular body of knowledge, but as a way of life. They define philosophy as a kind of practice or exercise in the expertise concerning what is beneficial. Once we come to know what we and the world around us are really like, and especially the nature of value, we will be utterly transformed.

Stoic Logic

Stoic logic is, in all essentials, the logic of Aristotle. To this, however, they added a theory, peculiar to themselves, of the origin of knowledge and the criterion of truth. All knowledge, they said, enters the mind through the senses. The mind is a blank slate, upon which sense-impressions are inscribed. It may have a certain activity of its own, but this activity is confined exclusively to materials supplied by the physical organs of sense. This theory stands, of course, in sheer opposition to the idealism of Plato, for whom the mind alone was the source of knowledge, the senses being the sources of all illusion and error. The Stoics denied the metaphysical reality of concepts. Concepts are merely ideas in the mind, abstracted from particulars, and have no reality outside consciousness. [4]

The scope of what they called ‘logic’ (i.e. knowledge of the functions of reason) is very wide, including not only the analysis of argument forms, but also rhetoric, grammar, the theories of concepts, propositions, perception, and thought, and what we would call epistemology and philosophy of language. Formally, it was standardly divided into just two parts: rhetoric and dialectic.

One of the accounts they offer of validity is that an argument is valid if, through the use of certain ground rules. It is possible according to them to reduce it to five demonstrable forms.

These are:

- if x then y; x; therefore y;

- if x then y; not x; therefore not-y;

- it is not the case that both x and y; x; therefore not-y;

- either x or y; x; therefore not-y;

- either x or y; not x; therefore y

Stoic Ethics

The Stoic ethical teaching is based upon two principles already developed in their physics; first, that the universe is governed by absolute law, which admits of no exceptions; and second, that the essential nature of humans is reason. Both are summed up in the famous Stoic maxim, “Live according to nature.” For this maxim has two aspects. It means, in the first place, that men should conform themselves to nature in the wider sense, that is, to the laws of the universe, and secondly, that they should conform their actions to nature in the narrower sense, to their own essential nature, reason. These two expressions mean, for the Stoics, the same thing. For the universe is governed not only by law, but by the law of reason, and we, in following our own rational nature, are by default conforming ourselves to the laws of the larger world.

In a sense, of course, there is no possibility of our disobeying the laws of nature, for we, like all else in the world, act of necessity. And it might be asked, what is the use of exhorting a person to obey the laws of the universe, when, as part of the great mechanism of the world, we cannot by any possibility do anything else? It is not to be supposed that a genuine solution of this difficulty is to be found in Stoic philosophy. They urged, however, that, though we will in any case do as the necessity of the world compels us, it is given to us alone, and not merely to obey the law, but to assent to our own obedience, to follow the law consciously and deliberately, as only a rational being can.

Virtue, then, is the life according to reason. Morality is simply rational action. It is the universal reason which is to govern our lives, not the caprice and self-will of the individual. The wise man consciously subordinates his life to the life of the whole universe, and recognizes himself as a cog in the great machine. Now the definition of morality as the life according to reason is not a principle peculiar to the Stoics. Both Plato and Aristotle taught the same. In fact, it is the basis of every ethic to found morality upon reason, and not upon the particular foibles, feelings, or intuitions, of the individual self. But what was peculiar to the Stoics was the narrow and one- sided interpretation which they gave to this principle.

Aristotle had taught that the essential nature of humans is reason, and that morality consists in following this, his essential nature. But he recognized that the passions and appetites have their place in the human organism. He did not demand their suppression, but merely their control by reason. But the Stoics looked upon the passions as essentially irrational, and demanded their complete extinction. They envisaged life as a battle against the passions which they regarded as emotional which had no real value, in which the latter had to be completely annihilated. Hence their ethical views end in a rigorous and unbalanced asceticism.

Virtue is founded upon reason, and so upon knowledge. Hence the importance of science, physics, and logic, which are valued not for themselves, but because they are the foundations of morality. The prime virtue, and the root of all other virtues, is therefore wisdom. The wise man is synonymous with the good man. From the root-virtue, wisdom, spring the four cardinal virtues: insight, bravery, self-control, and justice. But since all virtues have one root, those who possess wisdom possess all virtue, and those who lack it lack all. A person is either wholly virtuous, or wholly vicious. The world is divided into wise and foolish people, the former perfectly good, the latter absolutely evil. There is nothing between the two. There is no such thing as a gradual transition from one to the other. Conversion must be instantaneous.

The wise person is perfect, has all happiness, freedom, riches, beauty. They alone are the perfect kings, politicians, poets, prophets, orators, critics, and physicians. The fool has all vice, all misery, all ugliness, all poverty. And every person is one or the other. Asked where such a wise person was to be found, the Stoics pointed doubtfully at Socrates and Diogenes the Cynic. The number of the wise, they thought, is small, and is continually growing smaller. The world, which they painted in the blackest colours as a sea of vice and misery, grows steadily worse. [5]

We too, as rational parts of rational nature, ought to choose in accordance with what will in fact happen (provided we can know what that will be, which we rarely can—we are not gods; outcomes are uncertain to us) since this is wholly good and rational: when we cannot know the outcome, we ought to choose in accordance with what is typically or usually nature’s purpose, as we can see from experience of what usually does happen in the course of nature. In extreme circumstances, however, a choice, for example, to end our lives by suicide can be in agreement with nature.

The Stoics distinguish two primary passions: appetite and fear. These arise in relation to what appears to us to be good or bad. They are associated with two other passions: pleasure and distress. These result when we get or fail to avoid the objects of the first two passions. What distinguishes these states of soul from normal impulses is that they are “excessive impulses which are disobedient to reason”

Modern day Stoicism

Academic interest in Stoicism in the late 20th and early 21st century has been matched by interest in the therapeutic aspects of the Stoic way of life by those who are not specialists in the history of philosophy. There seem to be strong affinities between the central role that Stoicism accords to judgement and the techniques of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy or CBT.

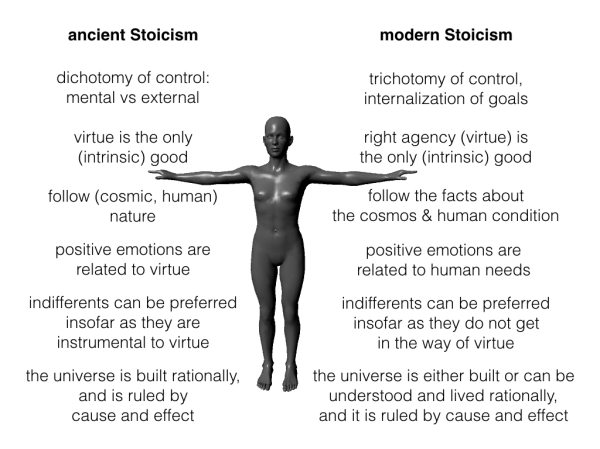

An example of what a modern Stoic would abide by here are a few examples:

- The realization of a trichotomy of control, leading to the internalization of one’s goals.

- Virtue reconceived as the ethical maximization of agency.

- A mandate to “follow the facts” about the nature of the universe in general and human nature in particular.

- An expanded conception of positive emotions, to include those that are related to fundamental human needs.

- An expanded pursuit of preferred indifferents, to include those that are only indirectly related to virtue, itself understood as excellence of character.

- A neutral stance on the fundamental metaphysics of the universe, with the Logos interpreted either classically, as a providential ordering principle, or in closer accordance with modern science, as the idea that the universe can be understood and lived rationally.

For humour I will add the modern day definition used by the urban dictionary.

Stoic:

Someone who does not give a shit about the stupid things in this world that most people care so much about. Stoics do have emotions, but only for the things in this world that really matter. They are the most real people alive.

Group of kids are sitting on a porch. Stoic walks by.

Kid – ‘Hey man, you’re a fuckin faggot and you suck cock!’

Stoic – ‘Good for you.’

Keeps going. [6]

Criticisms of stoicism

Friedrich Nietzsche taunts the Stoics in Beyond Good and Evil (1886):

“O you noble Stoics, what deceptive words these are! Imagine a being like nature, wasteful beyond measure, indifferent beyond measure, without purposes and consideration, without mercy and justice, fertile and desolate and uncertain at the same time; imagine indifference itself as a power – how could you live according to this indifference? Living – is that not precisely wanting to be other than this nature? Is not living – estimating, preferring, being unjust, being limited, wanting to be different? And supposing your imperative ‘live according to nature’ meant at bottom as much as ‘live according to life’ – how could you not do that? Why make a principle of what you yourself are and must be?”

This is pretty good, as denunciations of Stoicism go, seductive in its articulateness and energy, and therefore effective, however uninformed. (This is addressed in My Opinion)

The Stoics practised Apatheia, “absence of feeling”: a state of mind where the soul experiences no emotion at all. That was the only way in which the soul could be completely free. Any emotion would bind it to the body. Life is a cart pulled by dogs; you, as a dog, have a choice between struggling against it, thereby causing yourself grief, or simply running along, going neither too fast nor too slowly

Any sexual escapade or other enjoyment compromised one’s apatheia. In addition, even moderate pleasure could destabilize the soul, subjecting it to greater pleasure by consequence, which would ultimately end in pain. They equated sex with passion but since they considered passion to be weak, they still saw sex to be of value and equated happiness with it. This is one of the few paradoxes of life the stoics could not fully balance.

Criticisms of the Stoic theory of the passions in antiquity focused on two issues. The first was whether the passions were, in fact, activities of the rational soul. The medical writer and philosopher Galen defended the Platonic account of emotions as a product of an irrational part of the soul. Posidonius, a 1st c. BCE Stoic, also criticised Chrysippus on the psychology of emotions, and developed a position that recognized the influence in the mind of something like Plato’s irrational soul-parts. The other opposition to the Stoic doctrine came from philosophers in the Aristotelian tradition. They, like the Stoics, made judgement a component in emotions. But they argued that the happy life required the moderation of the passions, not their complete extinction.

My Opinion

I think the appeal of stoicism must be more pronounced in eras when the world seems to be unmanageable and resistance to our efforts to change its terrible course. Phenomena like global warming, the concentration of capital in the hands of the few, ideological polarization, persistent violence against civilians in acts of terror–the world does not seem to be inhabiting one of its more hopeful moments. Learning to take an attitude emphasizing having an even mind, and the importance of behaving oneself, locally, in a morally defensible way, even as the wider world goes to hell, can give us a sense of well-being that does not depend on the world’s being headed the right way. Detachment of this sort is one way of restoring a sense of control over our lives–that is, if I at least live rightly, to the greatest extent circumstances beyond my control permit that should be enough to find peace in grim times.

The truth is, indifference really is a power, selectively applied, and living in such a way is not only eminently possible, with a conscious adoption of certain attitudes, but facilitates a freer, more expansive, more adventurous mode of living. Joy and grief are still there, along with all the other emotions, but they are tempered – and, in their temperance, they are less tyrannical.

So is it the right position to take?

Some of it yes, but I don’t consider passion to be of lesser value since sometimes passion is what is used to portray what being human is.

There is a time to be Stoic and there is a time to cater for passion. Balancing the two together and you have a good healthy lifestyle in my opinion.

[1] http://www.iep.utm.edu/stoicism/

[2] http://www.philosophybasics.com/branch_stoicism.html

[3] A.A.Long, Hellenistic Philosophy, p.115.

[4] http://www.iep.utm.edu/stoicism/

[5] Ibid

[6] http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=stoic

Tagged: Philosophy, salsahavok

bagus artikelnya

LikeLike